Published on October 27, 2023

Disaster Preparedness and Community Resilience

Rebekkah Smith Aldrich / 24 October 2023

This article is part of the series of resources and webinars created by the Sustainable Libraries Initiative team, in collaboration with WebJunction, to support libraries in creating a more sustainable future.

Climate Action Planning requires attention in three main areas: mitigation, adaptation, and climate justice.

Climate mitigation, or the reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, was addressed in our previous article, “Getting Started with Climate Action Planning.” The next area, adaptation, requires strategies that enable personal, institutional, and community-wide preparation and adjustment in the face of the likely impacts of climate change on our local geography. We can no longer simply focus on our hopes that efforts will reduce the impacts of climate change on the future. Even if we did everything right to reduce GHG emissions in the next seven years, we will still experience increasingly severe weather patterns, heat waves, and systemic impacts on food systems, flood plains, and sea levels for the next three decades.

Confronting the reality of the damage that has been done to the climate and having a realistic idea of what the local impacts of climate change is an essential component to future-proofing your library.

Approaching Adaptation Strategically

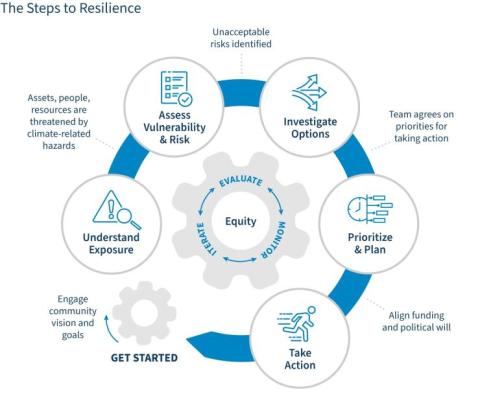

The U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit lays out a five-step process that you can use to build the adaptation section of your library’s climate action plan:

- Understand exposure: Identify assets, people, and resources that are threatened by climate-related hazards. Check out the Climate Explorer tool from the U.S. federal government to explore climate conditions projected for the coming decades for any county in the United States.

- Assess vulnerability and risk: Not all hazards are equally likely. Check your library and community’s adaptive capacity and estimate the probability of a hazard. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)’s National Risk Index is a dataset and online tool to help illustrate the United States communities most at risk for 18 natural hazards.

- Investigate options: Has this happened before in the community? Have other communities dealt with something similar? If money were no object, what would you do? What steps could improve resilience without spending any money? Is there a partial solution that you could implement now, and complement with further action at a later time? Explore case studies to see how people are building community resilience through the U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit’s Case Study collection.

- Prioritize and plan: What are the top three things that would increase the resilience of your library in the face of identified climate hazards? What are the top three things that your library can influence that would increase the resilience of your community in the face of identified climate hazards? What can you implement with existing resources? Who is working on similar things in the community already? Can you partner with them?

- Take Action: Implement. Monitor. Iterate. Share your story.

Disaster Preparedness

The steps above create a top-level plan to help prioritize the most immediate needs your library may have when it comes to adaptation. Building out a comprehensive adaptation strategy likely will require traditional disaster preparedness planning as well as considering how to position your library as a key asset in community resilience development.

Disaster preparedness is defined by FEMA as “…a continuous cycle of planning, organizing, training, equipping, exercising, evaluating, and taking corrective action in an effort to ensure effective coordination during incident response.“ This is an acute response plan that ensures an institution, or community, has thought through what should be done, step-by-step, in the face of the most likely hazards a locality may face. This type of plan sets a path forward to prepare and guide a library to minimize risk, loss, and chaos in the face of disasters.

Disaster planning can encompass:

- Staff training (e.g. evacuation routes; IT shutdown procedures; routine data backups; personal disaster preparedness)

- System redundancies (e.g. whole building generators; alternative energy and battery storage; cloud storage)

- Prioritized Recovery Plans (e.g. ensuring unique collections are salvaged first; identifying available technologies to get library operations back up and running)

- Crisis Communication Plan

- Incident Command Structures (e.g. who is in charge if the director is unavailable; where to set up operations if the building is completely compromised)

The New Jersey State Library commissioned the Librarian’s Disaster Planning and Community Resiliency Guidebook and Workbook, two phenomenal resources that were well ahead of their time to help libraries across the country to be better prepared. There are clear steps to help make your library more resilient so that you can return to operations quickly, as well as guidance on how libraries can help speed the recovery of their community by positioning themselves as key contributors to a resilient community.

Breaking down the barriers so that people can recognize that they often truly value the same things and can find ways to work together to make a community stronger, better, and more equitable is truly a defining hallmark of a resilient community.

Community Resilience

Community resilience is a long-term adaptation strategy at the community level focused on the “…the sustained capacity for communities to withstand, adapt to, and recover from adversity and disruption.” (Aldrich & Stricker, 2022, Chapter 23). Community resilience is often measured in the aftermath of disruption but must also be considered from the viewpoint of a community’s everyday cohesiveness.

The cohesiveness of a community unit is likely the most important contributing factor of community resilience. Social cohesion calls for increasing the respect, empathy and understanding that neighbors have for one another. It can be measured in the strength of relationships, a sense of solidarity, and available social capital through social networks.

Social capital is a set of shared values or resources that allows individuals to work together in a group effectively to achieve a common purpose. It is the glue that holds us together. On a personal level, you may be very familiar with social capital. It is evident in your willingness to help a friend, to pick up a prescription when they aren’t feeling well or chipping in at their yard sale. Scaling social capital is one of the chief challenges in our society. Breaking down barriers, increasing not just tolerance but true connection among neighbors is increasingly challenging.

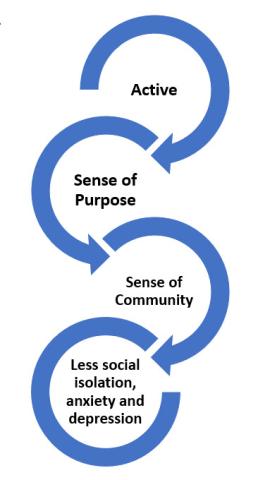

Civic participation is the other key to social cohesion. Helping folks come together to work on projects small and large to create a sense of purpose and a sense of community can lead to less social isolation, anxiety, and depression. Breaking down the barriers so that people can recognize that they often truly value the same things and can find ways to work together to make a community stronger, better, and more equitable is truly a defining hallmark of a resilient community.

The Healthy People 2030 project from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (OASH) sets data-driven national objectives to improve health and well-being over the next decade. It provides excellent resources to learn more about emergency preparedness, social capital, social cohesion, and civic participation.

As we work on equity, diversity, and inclusion in our spaces we should recognize that this is also climate justice work. Climate justice will be covered in-depth in an upcoming article in this series. Don’t miss the recording for Climate Justice, the most recent session in this series for more in-depth information on this section of your climate action plan.

Reference

Hirsh, Sandra, ed. Information Services today: an introduction. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2022.